It was nearly twenty years ago when retired zoologist John Darby, having spent hours at his computer summarising his data on Antarctic and yellow-eyed penguins one day, wandered the short distance from his home to the Wānaka lakefront. There were the usual waterbirds ̶ mallards, black-billed gulls, scaups, shags ̶ but then he saw a bird he’d only seen once before. With its slender white neck, black bill, blood red eyes, cheek frills and head full of feathers spiked like a punk rocker, there was no mistaking the pūteketeke, or southern crested grebe.

Extinct in the North Island, and with fewer than 1000 birds left in the South Island, pūteketeke are classified as nationally vulnerable by the Department of Conservation. Their numbers are up though, having increased from a low point of less than 250, a recovery that many attribute to the efforts of one person: John Darby.

Penguins in the bath

I go to visit John at his home in Wānaka. It’s hard to miss. In the front yard there’s a grandiose nesting platform in the shape of a grebe, made by a sculptor friend. When John opens the door to my knock, a black and white collie launches at me. “Sorry about that,” he says. “This is Patch. Our family dog died and I thought I would get a mature dog as a replacement. I considered that re-homing a farm dog might require less energy than training a pup. But he’s a bit of a handful. Come in.”

In the entrance there’s a painting of a grebe hanging on the wall, a photo of one in the lounge, and a series of filing cabinets labelled “grebes”. As we sit down, Patch wanders outside to worry an empty plastic flowerpot. Over a cup of tea, we chat.

John’s achievements are many and varied. There was the role of Zoologist at the Otago Museum in Dunedin, where he was appointed assistant director in 1971. He set up the Young Explorers Weeks and science workshop programmes for children, which led to the establishment of the first interactive science centre in Aotearoa. In his spare time, he spent close to two decades studying the hoiho, or yellow-eyed penguin. Astonished to find there was nowhere that was managed and protected for the hoiho, in 1985 he negotiated with the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) to purchase the largest breeding area on the South Island, on the Otago Peninsula. He was also made an honorary lecturer in the Department of Zoology at Otago University. “My children grew up with penguins in the bath,” he tells me.

John’s childhood was less happy. Born “out of wedlock” near Huddersfield, in West Yorkshire, John spent time in eight different orphanages and one short-term foster home.

He recalls that, “in all those experiences I never had the sense that anybody really cared for me, or that I had anyone to love. I never had a hand to hold, or any adult figure I could truly talk to.” He got into trouble a lot, running away often to try to find his mother. At the age of 15, despite doing well at school, he was placed on a dairy farm in Surrey, “because in those days if you were brought up in an orphanage, girls became domestics and boys became farmhands. It was brutally hard work as we had to milk the cows by hand.”

But his employers at the time did help him finally track down his mother. “She agreed to meet me at a railway station in London, so long as I didn’t try to follow her, or try to find out where she lived.” Perhaps feeling he’d been rejected yet again and not able to agree to what had been suggested, they didn’t meet. Now, he says, he can see that, like so many women at the time, she was saddled by society with the weight of a shame she could not carry. “In 1930’s England, what she did was considered abominable.”

Supernormal stimuli

Word on the street was that there was a single pair of grebes on Lake Wānaka who had tried to build a nest and breed in Roy’s Bay. But the rise and fall of the lake, coupled with large waves, meant they’d failed. John wondered if they could be encouraged to nest in the Wānaka marina if they had a secure spot. He read everything he could about pūteketeke and spent more than 100 hours watching and documenting them on Lake Hayes, near Queenstown. An accomplished white-water kayaker, he found he could observe the shy birds more closely from his kayak. In 2013, finished with his observations, he set about building an artificial floating nest out of plywood for the Wānaka pair.

“I put the first nesting platform out at 9pm, because I didn’t want anyone to see me towing this pile of what looked like compost behind my kayak.” He tied it under the marina and went back at 6am the next morning. “I couldn’t believe it – there were a pair of grebes going absolutely flat sticks improving on what I’d done.”

To trick the birds into using his nests over their natural ones, John had employed what is known as “supernormal stimulus”. He explains, “supernormal stimuli are exaggerated versions of the things creatures have evolved to desire.” For example, scientists have replaced songbirds’ small light blue eggs with bright blue dummy eggs; the birds will abandon their real eggs in favour of attempting to sit on the dummy eggs. The supernormal nests that John installed in the marina have been so successful that ten years on from the original pair there are now twenty nests, with 532 chicks fledged. The demand for housing has some grebes trying to build their nests on the back of boat transoms. In November 2020, grebes were spotted for the first time struggling to nest in windy conditions on nearby Lake Hāwea. A platform was anchored in a small inlet behind the lake’s dam and remains under the care of a local group initially led by the late Jane Forsyth.

The grebes’ nesting platforms are cleverly engineered. They are packed on the underside with donated swim noodles from the Wānaka swimming pool, a buoyancy solution that took a bit of tweaking. The birds struggle to get out of the water onto their nests ̶ they jump rather than climb ̶ and to compound the problem, a waterlogged grebe nest can end up weighing 20 kilograms or more. “As they build them up, they get heavier and heavier, and the platform starts to sink. The more it sinks the more they build it up,” John explains. A nest can end up being one big steaming compost heap. Vertical pieces of ply on two sides act like the bow of a boat swinging the platform to windward thereby protecting the structure from wind and waves, while the organic part of the nest is made by humans by weaving sticks through a layer of weed mat. This is then topped off with weeds and leaves gathered from the shoreline by the birds. The platforms are like little forts, moored in deep water, with the grebes in an elevated defence position so they can stab down with their beaks at any invaders. John believes all these factors has made the birds less “skitterish.”

In a 2001 New Zealand Geographic article, Bill Rea noted the decline of the grebes on lakes in Canterbury. “Human disturbance must be seen as a major factor … and these timid birds do not take kindly to power boats and jet-skis zooming past. I have been surprised when kayaking on the lakes that grebes in open water show clear signs of anxiety when approached, even at distances exceeding 100 metres.” But on Lake Wānaka during the Christmas rush when hundreds of motorboats are fizzing around, the pūteketeke barely increase the ruffling of their feathers. They are so unfazed by humans you can come within only a few metres from them and observe quirky behaviour like ingesting feathers to induce vomiting as way of expelling parasites. Then there’s the “weed dance”, a courtship display that starts with lots of head nodding. The birds dive and then surface with a beak full of water weed, rising like ballerinas in pointe shoes as the paddle furiously towards each other until, chest to chest, they proffer the weed, as if offering a dowry.

Weird puking birds

Throughout his life John has found solace in nature. As a foster child during the Second World War, he would deviate from the bridle path that took him to school. One day he was late and had to explain to the headmistress of his small primary school why. He said there had been a strange noise coming from a small copse and it had frightened him. A few days earlier a plane had crashed nearby and John thought the sound was something to do with the crash and might be German soldiers. His teacher kindly escorted him back to the woods, where they discovered the noise was the sound of a cuckoo. After that, she would often accompany him into the trees, teaching him the names of the birds and small animals they saw, firing an interest in the natural world.

After his failure to meet his mother when he was 16, John decided to leave the United Kingdom, as he thought his family history was always going to hold him back. He decided to run away again, and signed up for the “Ten Pound Pom” government-assisted migration scheme to Australia, falsifying his age as eighteen. The orphanage staff found out, and though initially aghast, decided to assist him. They helped instead apply to go to New Zealand which didn’t have an age limit, but required him to have a job offer, a sponsor, and most importantly someone who would act as his guardian.

When the boat docked in Wellington on a cold winter’s morning in 1954, John felt like his past had sloughed off him. He was seventeen and no one knew him; he was free to make a new start. The guardian assigned to him was the registrar at Lincoln Agricultural College, Gordon Hunt. “I will be forever grateful how they cared for me. Only one or two people were aware of my background and not having to explain myself was wonderful.” Life in New Zealand went swimmingly for a while, but almost a year after arriving, John woke up in Auckland Hospital’s Ward 22B, a victim of the polio epidemic. He spent seven months in there before moving to the Thomas Duncan Polio Hospital in Whanganui. After four months there, he left with a knee calliper on his left leg.

He returned to Lincoln University and completed his Diploma in Agriculture, graduating in 1958. He got a job as a technician at Ruakura Animal Research Station in Hamilton, where he found himself in “science heaven”, with his work shared between laboratory and field work. “The whole experience of being part of a research team was astonishing and wonderful.”

Today, John highlights the importance of teamwork in the Wānaka grebe project. He couldn’t have achieved what he has without the help of many people, and he is especially grateful to the Wanaka Marina Board. Students from Te Kura O Tititea Mount Aspiring College have helped build platforms, and local schoolchildren have decorated the plywood windbreaks with their artwork. On one kayak tour around the nests, a small boy asked John if he could be pecked by a grebe. “Why would you want to do that, it really hurts?” The boy had heard John on Radio New Zealand explaining how he got pecked when checking the bird’s eggs, and he replied, “because you said it was a privilege.”

For years, John has also written a ‘Grebe Diary’ column in the local newspaper, and everyone in town knows the pūteketeke. Not long ago, John was called by a local vet to retrieve one that had been found in the middle of Riverbank Road, quite a distance from the lake, by an early morning commuter. (John theorises with a full moon shining, the bird confused the road for a waterway; it was unable to take off again because grebes can only get airborne off water.)

But the birds received attention on an unexpected level last year thanks to Forest and Bird’s annual Bird of the Year / Te Manu Rongonui o te Tau competition. The conservation organisation holds the annual contest as a fundraiser, but for 2023 they upped the stakes and held a Bird of the Century event to celebrate its Forest and Bird’s 100th year. The pūteketeke found itself up against 75 species, including the iconic North Island brown kiwi and the beloved kākāpō, a two-time Bird of the Year winner.

A tough ask, until the British-American comedian John Oliver, host of HBO’s Last Week Tonight, fell in love with the pūteketeke and offered to run the bird’s campaign – which he did, enthusiastically. He bought up billboards in New Zealand, Japan, France, the UK, India and the American state of Wisconsin. A plane with a pūteketeke campaign banner flew over the beaches of Rio de Janeiro in Brazil. He had a giant pūteketeke puppet made for his show. He dressed up as a grebe and appeared on Tonight Show with Jimmy Fallon. He described them as “weird puking birds with colourful mullets”, praised their mating dances and marvelled at their birdsong (“like listening to an orgy of haunted dolls”). He dismissed one rival, the eastern rockhopper penguin, as a “hipster penguin”.

The 2023 Bird of the Century competition broke records, with more than 350,000 votes from 195 countries, well above the previous high of 56,733 votes cast. (Though fraud was rife, with 40,000 votes discarded after a single person voted them all for the rock hopper, perhaps insulted by Oliver’s slight). Forest and Bird received $600,000 in donations, more than six times higher than the 2022 total.

The Scientist

John was fifty when he received an invitation to travel from New Zealand to the UK to address a meeting of the British Seabird Group at Oxford University on the work he had been doing on yellow-eyed penguins. He received sabbatical leave from the Otago Museum and was able to accept an invitation for a six-week scholarship from the Danish Ministry of Cultural Affairs. While there, he decided to try again to reach out his mother, and with the help of the folk who had looked after him in the early 1940s, he found her in a rest home close to Leicester. John visited her several times. She had never married, fearing it would be discovered she had had an “illegitimate” child.

Meeting John for the first time was cathartic and he says she was able to let go of the shame that had shaped her life. Towards the end of his visits, she took him through the home introducing him to the staff and residents as her son. “She was just so proud,” John recalls. A few months after returning to New Zealand John received the news she had died.

He is eighty-seven now, and has been working on a succession and management plan so the grebes will be looked after in perpetuity. Recently, one of the grebe volunteers, Wānaka Primary School teacher Markus Hermanns, penned a tribute to John called ‘The Scientist’:

“Joy: A Scientist finds pure and sincere joy in what he does. Otherwise, why would he sacrifice most of his precious lifetime, risk his invaluable health on a daily basis and never stop moving forward for the sake of the object of his study … I feel honoured and blessed that I have the privilege to work with a scientist who has all these traits and thank him dearly for all his work and dedication.” The pūteketeke are surely nodding their grandly-adorned heads in agreement.

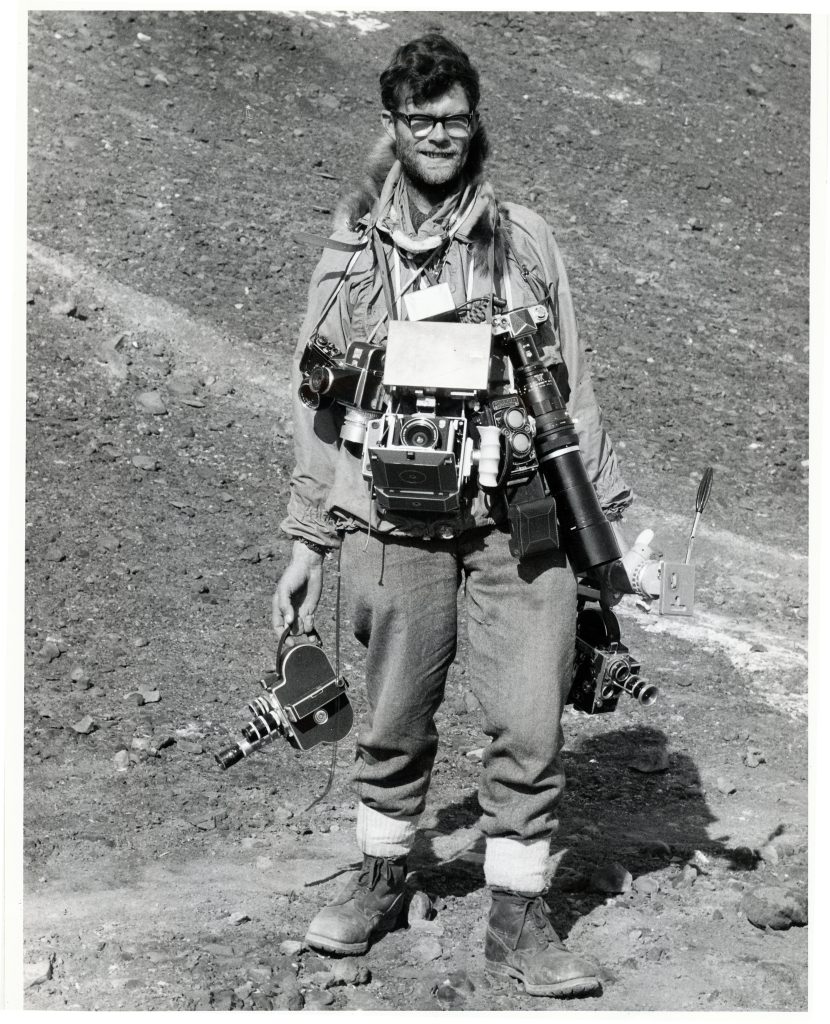

Words and photos (except where noted): Allan Uren