Size matters on the Interplanetary Cycle Trail.

I HAVE A PHOTO ON THE LOCK SCREEN OF MY PHONE. IN IT, OUR PLANET IS A PRICK OF LIGHT. THE ONBOARD CAMERA ON NASA’S JUNO SPACECRAFT SNAPPED THE IMAGE OF EARTH IN 2011 WHILE IT WAS ON ITS WAY TO JUPITER. I LOOK AT THE PHOTO WHEN THINGS FEEL TOO BIG. IT REMINDS ME THAT THINGS, HUMAN THINGS, IN REALITY ARE SMALL. IT HELPS ME WORRY LESS. IT HELPS ME REST.

The Otago Central Rail Trail retraces a rail line that once ran between Middlemarch and Clyde, carrying timber, wool, grain, livestock and fruit into the Otago hinterland. Trains fell out of favour and the tracks were pulled up in 1991, but the route was preserved, re-opening in 2000 as Aotearoa’s first Great Ride. The 152-kilometre-long track is a stunner, with big sky vistas, weather-sculpted rock and historical relics. There are gold tailings, heritage fruit trees descended from apple seeds spat from carriage windows long ago, and even a display of Miocene-era petrified wood housed in the ‘Ladies’ Waiting Room’ at Galloway Station. And there are planets, all of them.

We have Ian Begg to thank for those. His grandfather was John Campbell Begg, a respected amateur astronomer, fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society, and a co-founder of Dunedin’s Beverly-Begg Observatory astronomical observatory. Like his grandfather, Ian is fascinated by the scope of the universe.

“In school, we saw the solar system on a piece of A4 paper as the sun with the circles around it,” he says. These “educational” illustrations sometimes showed (or tried to show) the relative size of the planets, but the relative distances between them was either incorrect, or not accounted for at all. Like those old “blueberry muffin” models of the atom, they not only lacked accuracy, they lacked awe. As Ian puts it, “they didn’t show the vastness. It’s so important both the dimension of each planet and its separation from the sun match in scale, otherwise it’s meaningless,” he says. Tricky in A4, but possible over 152 kilometres.

Today, the Interplanetary Cycle Trail is a 100-million-to-one scale model of the Solar System that runs the length of the Otago Central Rail Trail. It was Ian’s idea, though the concept came to him before he settled on a venue. He wanted somewhere big enough to replicate the Solar System to scale, but a road wouldn’t do. He didn’t want people speeding from planet to planet without really taking in the distances between them. “Then I thought of the Rail Trail. It was perfect for it.”

Ian took his idea to the Otago Central Rail Trail Trust, and after a bit of back and forth, as trustee Ken Gillespie remembers, “we said, he’s actually serious! We’d better have a look at this.” They did, and they liked it. The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment offered support through the Unlocking Curious Minds fund, Ian sent out a (very specific) brief to local engineering firms and Wire Art in Lake Tekapo, and soon nine planets were ready for deployment.

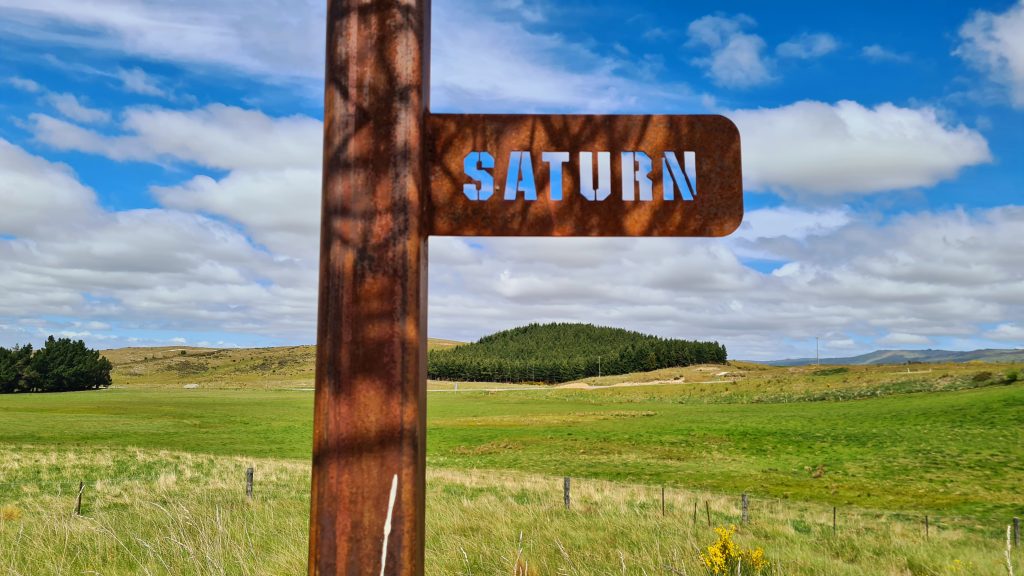

Like their real counterparts, each one is different. Venus looks like a mottled red cricket ball, while the other terrestrial planets, Mercury and Mars, are represented in negative space, as holes punched through sheet metal. So, apparently, is Pluto, though I can’t confirm this, I’ve never found it. Rumour is, it’s 2.4 centimetres wide and on the outskirts of Alexandra. (Yes, Pluto is included despite being demoted to a dwarf planet by the International Astronomical Union in 2006. It’s still a planet in our hearts.)

The Jovian giants — Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune — are rendered in barbed wire, which gives them a steampunk / actual-punk feel suited to their ammonia-ridden hostility to human life. The Sun, located in central Ranfurly, proved problematic. To keep it to scale, it needed to be 14 metres in diameter, which raised resource consent issues. For now, it’s represented by a circle of waratahs joined by yellow rope. The trail passes straight through its middle.

The highlight though, is Earth, a silver ball with the continents etched on it in gentle relief. It is twinned, as we are, with a moon. And, thanks to an ‘Eclipse Shadow Board’, if you stop by between 0800 and 0900 hours during the March and September equinoxes, you’ll see the shadows of Earth and Moon merge in a mini lunar eclipse.

Ken and Ian set out the Ranfurly to Clyde leg first, in 2017, doling the planets out from a trailer over the course of a couple of days. It might have only taken one, Ken says, but they had to hang out a bit to be there at the right time to get the angles sorted for the Eclipse Board. The Ranfurly to Middlemarch version went in the following year.

The installation is not only one of the cooler cycling experiences out there, it’s a mathematician’s dream ride. At 100-million-to-one, one centimetre on the trail is equivalent to 1000 kilometres in space. This puts Mars at three kilometres from the sun, while Pluto is 60 kilometres away. Each turn of the wheel is 200,000 kilometres, and if you’re pedalling along at the standard 11 kilometres per hour, you’re going faster than the speed of light – a helpful fact to hold on to when you’re riding into a heart-breaking headwind.

It’s an existentialist’s dream too. As Ian points out, unlike that classroom sheet of A4, or rows of numbers in a textbook, physically riding from planet to planet gives you a visceral sense of being amongst it, and a dollop of perspective. When NASA Astronaut Mike Hopkins, who has logged 166 days in space, checked out the trail in 2018, Ian noted that the “distant” International Space Station orbits 400 kilometres above the Earth’s surface, which is the equivalent to 4mm, or the length of a grain of rice, on the trail. Meanwhile, Alpha Century, the nearest star to us, would be 400,000 kilometres away. “People say it’s in space, it’s not even in inner space!”

Riding away from Earth, I looked back. It reminded me of ‘Earthrise’, the photo taken from lunar orbit by astronaut Bill Anders during the 1968 Apollo 8 mission. ‘Earthrise’ shows our planet, half lit by the sun, coming into view above the desolate grey horizon of the Moon. The image is credited with changing how we see our home planet, and ourselves. As Bill put it in an interview with The Guardian, “It didn’t take long for the moon to become boring. It was like dirty beach sand. Then we suddenly saw this object called Earth. It was the only colour in the universe.”

The Interplanetary Cycle Trail kind of does this too. We are very small, and it’s a long way to anywhere else. But in our planet, and our neighbourhood of planets, we may have something precious. To roll through them one by one, in some version of real time, gives us a glimpse of this. We are Earthlings. Greetings.

WORDS & IMAGES: LAURA WILLIAMSON