Aotearoa New Zealand’s curious connection to a beloved children’s classic.

Anyone who has ever lulled children to sleep with the bedtime story Goodnight Moon will not be surprised to hear that its author, Margaret Wise Brown, was an unusual woman. It’s a strange book.

There’s a wee bunny in bed in a “great green room”, one full of objects and other creatures. Some, like a dollhouse, two kittens and a comb, are fairly understandable. Others, like a tiger-skin rug and the mute elderly bunny-lady on a rocking chair, less so. The reader is invited to say good night to a number of things, including the eponymous moon, a pair of mittens, the whole house, the bunny lady and, to “nobody”, which is mildly unsettling. Then again, so is childhood. The story works beautifully. It’s an ode to poetry and whimsy and to the altered reality that is the mind of a sleepy toddler.

As well as being a genius writer, Brown lived quite a life. It’s a long story, but suffice it to say that if the UK’s Daily Mail publishes a headline like this about me after I die, I will consider my time on earth to have been well spent: “Secret life of children’s author Margaret Wise Brown: Wild life of Goodnight Moon writer who hated kids and had affairs with a female poet and a married man.” Despite what was obviously a busy private life, Brown wrote a lot of books. In 1946, LIFE magazine named her the “World’s Most Prolific Picture-Book Writer”.

Lesser-known than Goodnight Moon, but equally loved, was 1946’s Little Fur Family. It tells the story of a “fur child” (just go with it). He lives in a tree with his fur family, who, despite their hirsuteness, put on fur coats before they go out. While exploring in the forest, he meets another “little tiny tiny fur animal”, his very own Mini-Me, and gives it a kiss on the nose. The tale ends, again, at bedtime, with the hairy lad tucked into bed, “all soft and warm”, by his parents.

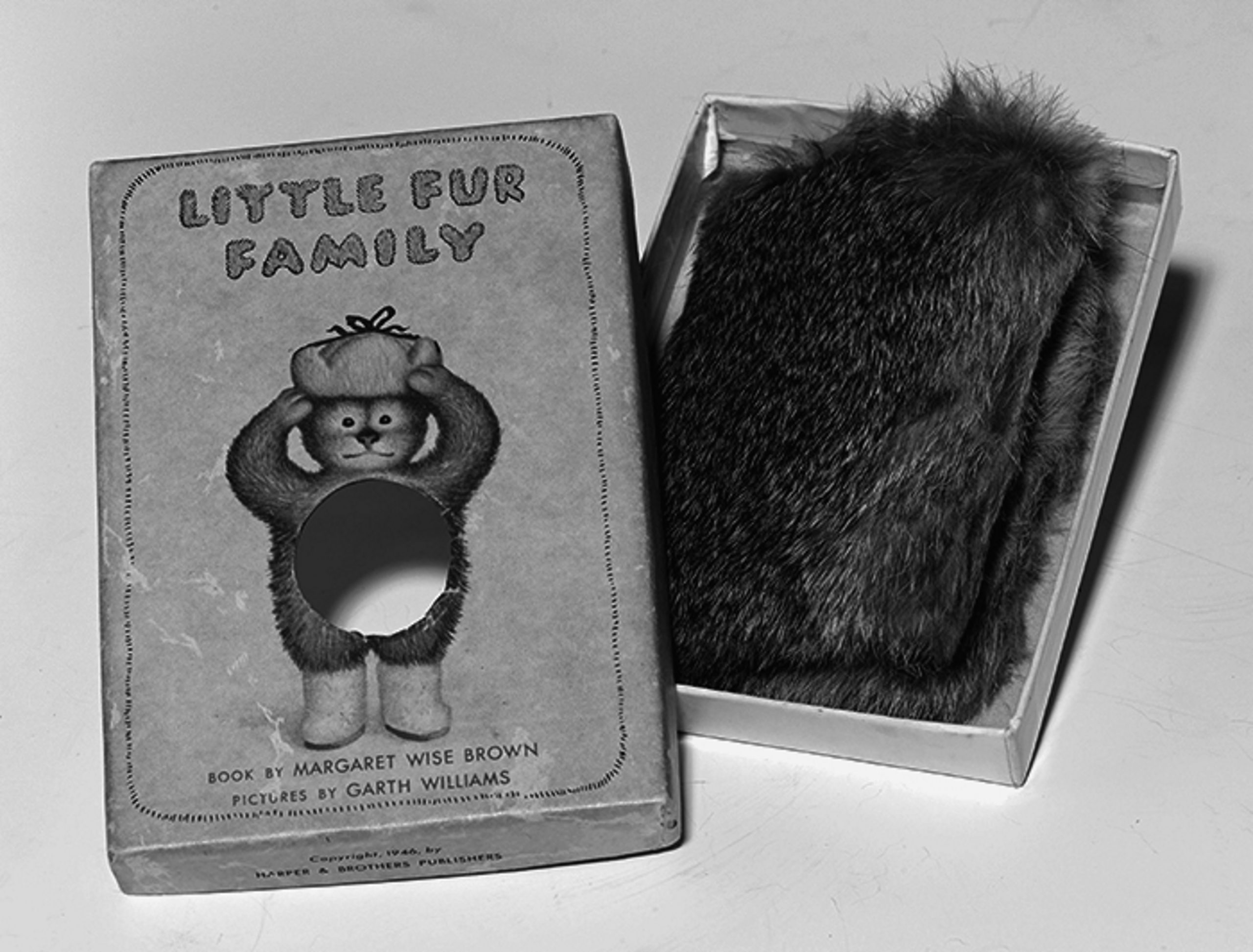

Not only is the family furry, so is the book. The main text comes inside a sleeve with a hole where the boy’s belly is. The inner book is wrapped in fur, which pokes through the cutout, creating a real fur belly for the fictional fur child. A recent profile in The New Yorker, called it “Brown’s most aesthetically provocative book”, and the first print run was particularly provocative. Brown insisted that it come wrapped in real rabbit fur, and that fur came from New Zealand.

Adults were perplexed, kids overjoyed. One oft-repeated story tells of a child who tried to share his dinner with the book, thinking it was a real pet. In December of 1946, LIFE called the “miniature volume bound in New Zealand rabbit fur” the most promising new Margaret Wise Brown title. This was high praise for a work by an author who had, at that point, sold more than 830,000 books in her career. It looked and felt so good, LIFE noted, the publishers had ordered an enormous initial run of 75,000 copies.

This begs a few questions, the first one being, why rabbits? Seems Brown had a thing for them. The choice of bunnies as protagonists like those in Goodnight Moon is one she made more than once. The Runaway Bunny (1942) is about a bunny who tells his mum he wants to run away. One of the framed images on the wall in Goodnight Moon’s great green room is a tableau featuring a mummy rabbit trying to catch a baby rabbit with a carrot-baited fishing rod. It’s an image from The Runaway Bunny, which creates a kind of bunny Inception. Bunnies within bunnies.

Brown also had a thing for hunting. As well as drinking gin martinis, one of her favourite pastimes was “beagling”, which involved setting packs of beagles loose on the trail of frightened Oklahoma jackrabbits, imported specially for the activity.

Which leads us to another question: Why New Zealand? It’s hard to know. But the country was, in the 1940s, battling a major rabbit plague, so we had plenty to spare. And, unlike Americans, we just don’t like bunnies here, no matter how cute.

There were a few problems with the covers. For one, moths got into the publisher’s warehouse and ate quite a few copies of the first printing. Also, there was some concern about where the bunny fur had come from. Someone estimated that the initial print run equalled 15,000 rabbit deaths, and the publisher had to reassure at least one bookseller that “no rabbits had perished expressly for the sake of the book.” In her memoir My Own Two Feet, the American author Beverly Cleary describes working in a bookstore that was trying to unload 500 copies of Little Fur Family. She and her colleagues sold them all by claiming, “that the fur jacket was made from the pelts of kangaroos, varmints in Australia, and that no good American rabbits had been sacrificed.”

She should have kept one. Today, a rabbit-fur-bound first edition of Little Fur Family will set you back a sweet $1800 US dollars. Then again, since rabbit eradication hasn’t really succeeded in New Zealand, you could go one cheaper and buy a modern copy for 20 bucks and wrap your own. Goodnight bunnies!

LAURA WILLIAMSON