Liz Breslin goes ghostbusting in two of the South Island’s haunted hotels.

We are not Kesha in popular reality TV series Conjuring Kesha, who says, in the trailer, “a lot of things have happened that are weird, but I’m like, give us more.” We are not the beloved Ghostbusters men or the flopped Ghostbusters women. We did not audition for Kristen Stewart’s Paranormal Experts show and we are not members of the New Zealand Strange Occurrences Society. We have no qualifications in ghost hunting whatsoever and actually are not interested in hunting them at all. We are ghost-curious world lovers and this is what happened when we set out to visit some of the spirits of the South.

The Glory Hole

The fog is low as I turn right for St Bathans, inland on the Pigroot between Dunedin and Wānaka, the perfect place to meet for a ghost-visiting date. I arrive first, to learn that we will be the only guests at the Vulcan Hotel for the night. Settling in for a pint of Rose’s Ghostly Pale Pale Ale made by the Otago Brew School, I chat with Amy, the newish leasor, about our quest to visit Rose.

Having been here nine months, Amy’s not had any confirmed ghost sightings, but certain sounds and movements have had her wondering. Also, there’s the small mystery matter of the book. She disappears upstairs to come back down with a hand-sewn story she found in the dresser next to her bed. ‘The tragic tale of the Vulcan ghost’, by a Lady.

Amy does not know who wrote this or how it got there. Steve, who has popped in for a double order of fish bites and chips for takeaways–and a Woody while he waits–does not know either. Steve owns the house with the old jail down the road. He tells me he has only seen Rose once, maybe, he was walking home with Poppy, his missus, and one of their friends took a photo of them, and Poppy had one of those big black three-quarter coats and the photo came out with spots on the back and someone said they were orbs.

(An orb is “a misty sphere of residual spiritual energy”. I learn this from Ghost Hunt, a cult-status 2005/6 TV series that investigated iconic city-based ghostly locations in New Zealand, such as St James Theatre in Wellington and Dunedin’s Larnach Castle.)

Another time, Steve dressed up in a long black wig and scratched the window of Room 1 at night when a friend of his was staying there to scare them. It’s not the same night that Steve himself was attacked by one of the wild pigs of St Bathans, but that’s another, true, story.

Room 1 faces directly onto the street, separated by two doors and a corridor from the hotel bar. There is a ski pole by the door to the outside in case of wild pigs. A bed, a bedside table, a sink, a dresser and a chair. The chair is by the window and it feels like we shouldn’t put anything on it or sit there ourselves. We set up the gifts we have brought for Rose on the dresser. Kat has brought a doily and an LP on which the first song is ‘Rose Garden’. My contribution is some colouring pencils and paper in case Rose wants to leave us a note. We want to make sure she knows we come in friendship, and what nice long-skirted lady doesn’t love a nice doily?

Was Rose a nice long-skirted lady though? Six out of nine people I told about coming to St Bathans mentioned the sex worker ghost and while I suppose it’s progress that they didn’t call her a prostitute, I feel like it shows a lack of imagination and respect to think that’s the sum total of who we’re here to call on. (Full disclosure: we did joke about having a threesome with her and now I feel terrible about it.)

‘The tragic tale of the Vulcan ghost’ depicts Rose as Rosie O’Dowd, a young woman who worked at the hotel from the age of twelve, since “neither parent was happy nor any longer handsome, both worn out by the burden of staying alive in a harsh and unyielding climate”, and what’s a girl supposed to do? The daily slog, apparently, and then she met Mr Piers Osmond, a suave gentleman caller/grandiose narcissist who always stayed in Room 1. “Piers Osmond invited Rosie to his room to view a special treasure,” says ‘The tragic tale’. The special treasure was a snow globe which Rosie got to keep. Things she didn’t get to keep: Piers, who disappeared, leaving Rosie pregnant. Her sanity, as she wailed and fretted outside Room 1. Her baby, who died during being born. And maybe even her life. She disappeared the very next day and has never been seen again. The story ends with a suggestion of Rosie’s spirit being trapped in a snow globe given to a young girl who nearly disappeared over the edge of the cliff into the Glory Hole. This is absolutely what St Bathans’ famous Blue Lake was called during mining times and I for one would be happy to revive the name.

We eat delicious fish and chips in front of the fire. We decide not to go outside because it is more than a little chilly and the fog is still getting in the way of the moonlight. Also, wild pigs. We finish our pints with a game of puritanical snakes and ladders. I climb up a ladder from confession to forgiveness and slide down a snake from mischief to woe. Ill-doing leads to trouble. Penitence to grace. Back in Room 1 we put on all the clothes we can find, turn both the heaters up, call goodnight to Rose and turn out the light.

We wake up freezing and late. Ice on the inside of the windows of Room 1. Both the heaters are cold. No water comes from the sink. Or the shower down the corridor. But thankfully I already filled the kettle for coffee. And it works. So if the power’s on, why did the heaters both turn off? They were not on timers. After a walk around the stunning moonscape of the Glory Hole we read that it was down to minus seven degrees overnight, which might at least explain the pipes. We check out and leave the doily on the dresser. The day is blue and stunning for the outward drive.

Bluffing

There are good people everywhere and there are great people in Bluff. Some of them are staying at the Foveaux Hotel, lots of them have families who have run the Foveaux Hotel over the years, all of them are willing to chat about the existence, and the identity, of the Foveaux Hotel ghost.

I have a disgusting hangover (the martinis were excellent, the aftermath is not) so I am, for today, absolutely willing to embrace the life and work of top ghost-contender Mary Cameron, who used to run the Temperance Boarding House on this very same site. #spiritsnotspirits.

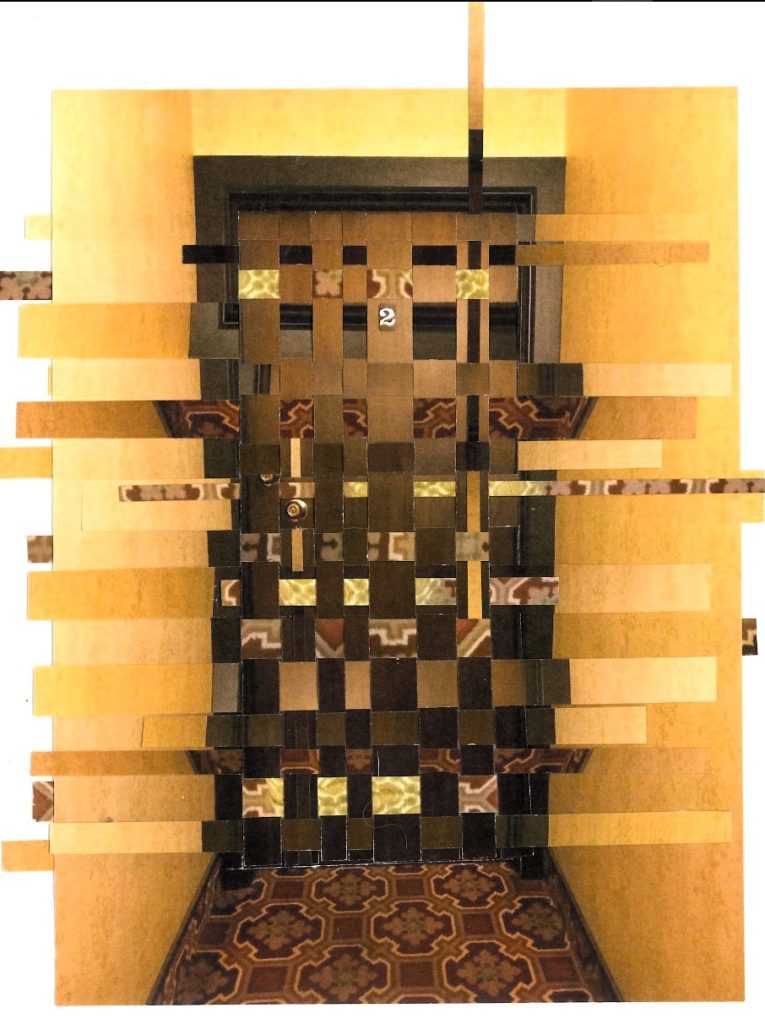

As we approach the front door, Kim calls a hello from the balcony and shortly we’re all standing in the lobby exchanging stories. It turns out that Ritchie, who is working with Kim on the rigging, is staying in Room 2, which is where Mary has mostly been felt, or seen. Which is great because Mary loved a man in uniform and wait, does rigging require uniform? And is this the pounding of my temples, or, no, yes, there’s a definite scratching happening on the front door. A definite scratching that’s getting … louder… and more … insistent. Eli opens the door. Nobody there. We look at each other. They close the door. My head hurts. We look at each other. We look at Kim. She smiles. We open the door. “Hi Ritchie.”

Kim and Ritchie make us feel immediately at home, as do Pam and Mike who are the current owners of the Foveaux Hotel. As does our new BFF Dylan at the Eagle Pub who wants to hang out with us because his sister is a lesbian. Everyone we meet at the RSA . And Hank, who singlehandledly runs the Golden Age Tavern, who introduces us to Karen, whose family used to run the Foveaux Hotel.

Karen tells us about the ghost she saw there when she was a girl. Says there was a kind of lounge up top between the bedrooms, and none of the family liked being in there alone. One day she saw a woman there. Holding, in one hand, a child’s hand. A hat box in the other hand. A large hat on her head. But not a Mary.

Williamina Dean took the train down to Bluff in 1895, hatbox in hand, to pick up Dorothy Edith Carter, a baby who was later found dead in her garden. Dorothy died, according to the court, of an overdose of the kind of drug people gave babies to soothe them and keep them quiet. Laudanum maybe? Which doesn’t stop Karen telling us about how Minnie brutally murdered the children in her care with hat pins through their fontanelles. People outside the courthouse during Minnie’s trial sold miniature dolls inside little hatboxes as souvenirs. She was the first and last woman hanged in New Zealand and her crime was infanticide.

It does not help that I read that hat pins didn’t come to Aotearoa until after Minnie swung. After closing time, I lie awake and stare at the artwork on our wall. Bright collage butterflies over beigeish greekish tiles with fake burned edges like the ones on the teabag-browned maps I made as a kid. Bad art is haunting me. I listen to every creak. I really really really need a wee because I have been hydrating so very well for temperance purposes. But I can probably just go back to sleep. No. I concentrate on the carpet as I pad down the corridor to the toilets. If I don’t lift my eyes then I can’t catch a ghost in the corner of them. Right?

Another day, another chance to find the stories. I’m not hungover anymore, and we’re keen to track down Mary Josephine Hill, another contender for the spirit who has reputedly done things like cleaned up spilled milk (well, there’s no use crying over it) and rattled doors at the Foveaux Hotel, but the archives are as silent on this Mary as they are on the last. By the archives, I mean we’ve searched Papers Past online, asked around in town and braved our way past the dreamcatchers and man cave signs in the giftshop and into the Bluff Library. There we find a handtyped book interviewing three local women, but none of them are called Mary and there is nothing about the ghosts.

Friday night at the RSA, we’re too busy discussing pony club ribbons and our karaoke songs of choice to get much into the ghosts, though I wonder aloud why Mary didn’t choose to hang out here if she was after a man in uniform, since it is literally next door to the Foveaux Hotel. Mary apparently fancied all her brother’s friends when he brought them back from the war, but now I think about it, which war? If these walls could talk. There is so much to learn.

We end the evening leaning on the lobby bar while we wait for the kettle to fill for our water bottles. Right at home. It’s a last chance to ask Ritchie about his long-term living arrangement with Mary. They’re down here rigging for a couple of months. “I’ve got Māori family,” he says, “so we tend to think a bit differently about these things.” He tells us how he talks to Mary as he comes and goes from the room. And that he sorts the pillows a certain way at night, away from him but comfortable, inviting, in case she’s there and tired.

WORDS: LIZ BRESLIN

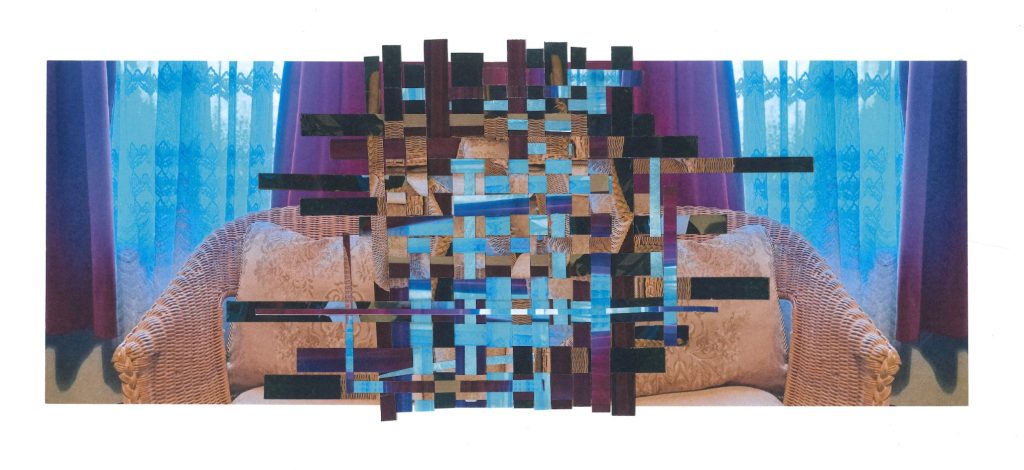

ART: KAT HEAP