Cromwell, Aotearoa New Zealand, 2219

Once upon a time, Great Grandmother told you stories.

Stories about a world – she said it was this world, only different – where the gulls would snatch children’s food, but not their hands. Where humans were the top of the food chain and did whatever they wanted. Where they ate and drank from plastic wrap and plastic bottles and brushed their teeth with plastic brushes with paste that came in plastic tubes. Imagine! And the water was clean, she said, so clean you could drink it right from the source. You could even buy it, clean, in plastic bottles.

You’re looking at one of these bottles now. The plastic is cleaner than you are. It’s taken the weather better than you have. But you’re getting older and everyone knows that people biodegrade eventually. Not like plastic.

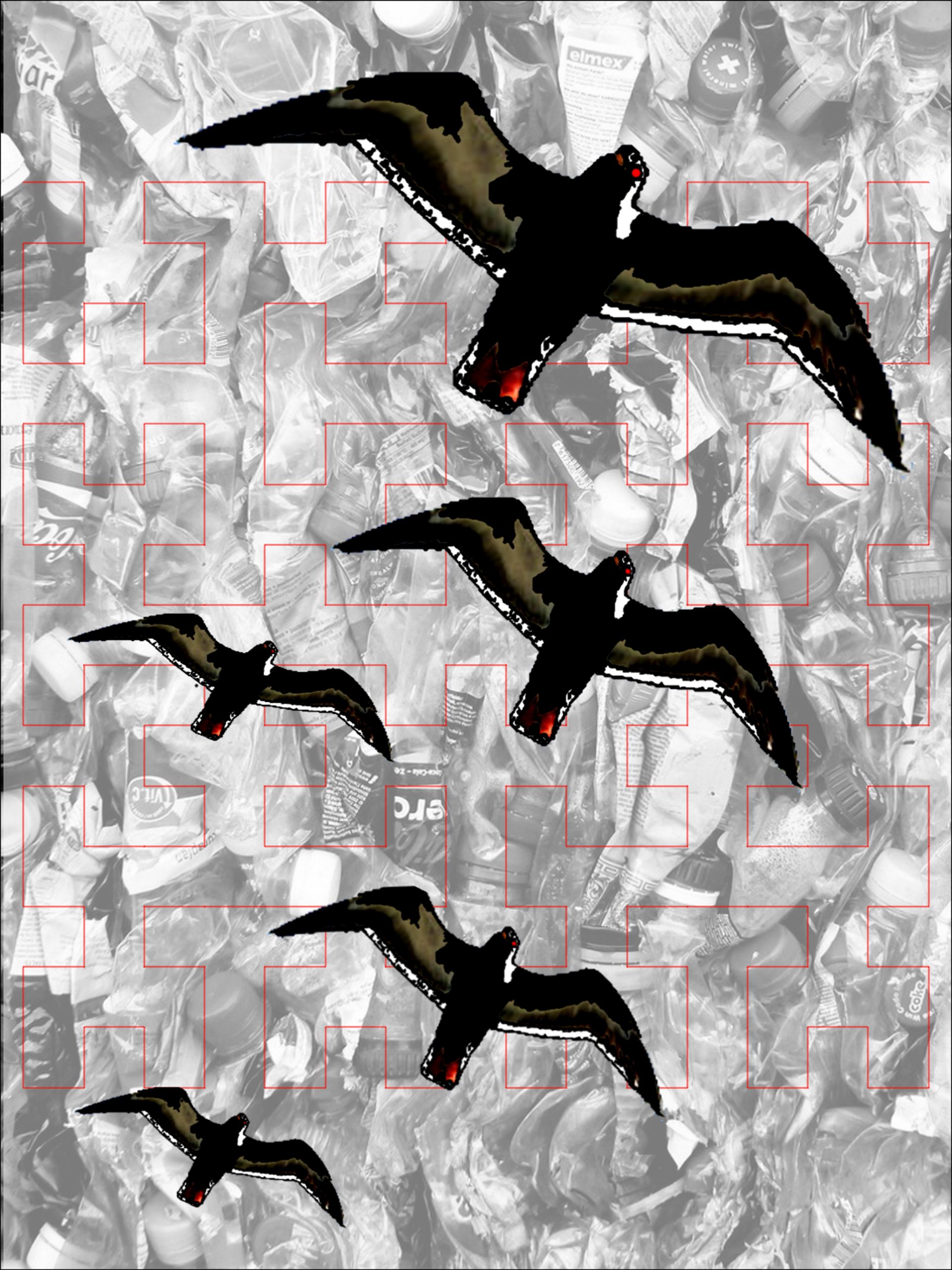

You look at the gulls standing on the plastic oil can pile, about fifty paces to your right. There’s three of them and their black, shining eyes don’t betray which way they’re looking. Their feet scrape and slap on the faded yellow plastic and they flap their wings, impatient for action. Maybe they know you’re here. Maybe they’re waiting.

It hasn’t rained in days and the others sent you to find the lake, to bring back plastic bottles of water to purify and drink. It takes time to remove the micro-plastics and the chemical contaminants from the water. Camp water supplies are almost out and the others expected you back before the sun reached its peak. But there’s been a delay. This small pack of gulls has been on your trail since dawn. You saw their dull brown outlines in the distance, specks above the mountains in the searing heat of high summer. The piles of plastic all around you are the perfect place to hide. Sticky fluid sits in the bottom of any plastic container that’s still watertight and it all reeks so badly, you feel like it puts up a resistance, like you have to push your way through the air. But maybe that’s hunger, dizziness, slowing you down.

Hunger speeds the gulls up. They’re hunting. Great Grandmother told you a story about gulls eating scraps of human food, nibbling at things left behind because food was so plentiful back then that humans left a lot of things behind. They piled the left-behinds into big heaps that filled the land and the gulls would hover over the heaps and squawk loudly. Great Grandmother said the gulls didn’t eat plastic back then, just the food scraps. The other kids didn’t believe her. Gulls have always eaten the plastic and they need blood to dissolve plastic in their stomachs. Everybody knows that. But Great Grandmother insisted it was different in her day. She said humans made plastic – that humans loved plastic. That kids like you would play with moulded plastic inside nests made of blocks and concrete.

One of the gulls squawks a shriek of excitement and you worry for a moment that they’ve spotted you, but they’re just fighting over a small, clear pottle with thick, red fluid swishing around the bottom of it. You swallow. Your throat is dry and you resist the urge to cough.

You take cover under a giant peach (that was a kind of fruit, once, and they weren’t made of plastic, Great Grandmother said). Tall pillars with remnants of other giant fruits huddle around it, but the giant peach is the only whole landmark discernible for miles. The others told you there was water not far from here – half a day wading through the plastic heaps at the most. But since the gulls showed up you’ve been reluctant to move from the peach. One gull can cause a nasty injury, one that could get infected. Three gulls could overwhelm someone of your stature. Picking and scraping at your eyes and mouth, they’d dig with their thin-webbed and tiny-clawed feet until they drew blood and then the frenzy would begin.

You had a sister once. When you were younger she liked to dig through the heaps to find scraps of food and she’d concentrate so hard the whole world around her would disappear. She didn’t hear when the gulls came and the other kids screamed and ran for cover under the rocks.

Great Grandmother was still alive then too. She cried. A waste of good water, crying like that, the others said. But she cried anyway. That’s when she told you about the gulls in her time, the ones that would steal scraps of food, but food wasn’t so scarce so humans didn’t mind. Sometimes, they’d throw food to the gulls, just to watch them fight each other. The way they’d hover, then dive. Hover, then dive. She told you so many stories about her time – the others told you they were fantasies. Humans couldn’t have made a world like this, they told you, look at our soft bodies, our small eyes and thin limbs, humans could not have made the plastic, could not have killed trees and filled lakes of clean water with dirt and poison and plastic. Humans are simple and innocent creatures, they told you.

But you wondered about Great Grandmother’s stories. Stories about humans with machines that took them great distances in short times, about huge places with lines and lines of food neatly wrapped in little plastic packages to take whenever you wanted them. With lights that shone at night and machines that moved through the air faster than the gulls. You loved her stories, back then. They took you to a place that felt safe and warm and full.

You shift from lying on your stomach to kneeling. The gulls have their backs to you and they’ve moved slightly further away. It could be a trick – gulls are clever hunters – but they seem absorbed by the pottle with the red stuff in it. They’re fighting among themselves and making a lot of noise. You stand up and put a hand on the peach. The ground below you moves and slides beneath your feet. It’s made of flattened plastic. The top parts are pastel-coloured, but you can see other plastics below in their brighter, un-sun-bleached glory. The heap you’re standing on slopes downwards and in the distance, there appears to be a drop-off. This could be the water, you think. It’ll be hidden underneath a layer of floating plastic – this long, flat layer is a tell-tale sign of water.

The sun is low and hot. You draw long, shallow, shaky breaths and feel dizzy. Long, shallow, shaky breaths. Long, shallow, shaky breaths. If you fall asleep beneath the peach, the gulls might find you. You’re not used to sleeping by yourself and the idea makes you feel soft-fleshed, like a rat caught on its back, with its bloated, pink belly in the air for all to pick at. You remember your sister and she reminds you to concentrate.

You’re not sure when you decided to do this, but now you’re running, no, sliding, across the pile of plastics. You’re on your feet most of the time, but occasionally, you bruise your arms and sides rolling and sliding sideways down the heap. A shrill cry breaks out behind you. The faded-pastel-coloured plastics paint a colourful blur all around you as you run, stumble and tumble down. Your foot hits something solid, something metal, and you feel blood rushing. You hope the blood is not leaking out, not leaving a bright red trail behind you. The gulls would smell that, the gulls would find you then.

Through the blur, you can see the plastic has started to move with you. Pottles and plastic cans, sticky tumbleweed balls of thin, clear plastic and a bright blue piece in the shape of an animal with a flat tail and a long, rounded nose, chase you down the slope. You and the plastic are gathering more speed now. Sometimes you’re up, running with your legs, other times you’re down again, sliding on your side or your back. You see a brown shadow swoop for your head and miss. They are here. They’re silent because they’re serious. They’ve eaten their fill of plastic and now they need your blood to help them digest. Everything is moving at speed, so you only see pastel-multi-colours and flashes of dark brown, but you can imagine their distended stomachs and hooked beaks.

At once, everything is shockingly cold and you gasp for air, but none of it comes. You feel your insides clench and your immediate thought is that the gulls have pierced your flesh and this is what dying feels like. You float to the surface and spit out water, managing to swallow enough air to submerge yourself again, moving in the water instinctively, though you have never seen this much water before. This is it, this is the lake, you’re here.

The water stings your open eyes, but you see a large piece of soft plastic floating nearby. The gulls penetrate the water, diving sharply near you. One of them bites your leg and again, you feel the rush of blood and this time you see red, smoke-like trails clouding the water around the fresh wound. The soft plastic is thick, thick enough to soften the blow of the gulls, but soft enough to move and wrap around you so that the gulls get caught in it as they try to dive for you. They start to take it in turns to dive for your head, pushing your face underwater so that you have to breathe fast, taking in air whenever you can. You can’t breathe under the water and this sparks a novel thought: you might die under the water. And you’ll be the first person you know who dies from too much water.

You bunch up more of the sheeting around your body, like a blanket. You notice that you’re holding the plastic creature, the blue one with a flat tail and a long, rounded nose. You must have snatched it up as you tumbled through the heaps, and you’re not sure why, but it’s comforting to hold.

It reminds you of another of Great Grandmother’s stories. The one about the swimming pool. A neat rectangle of blue water, with plastic playthings floating in it, back when humans floated in water for fun. Great Grandmother would wrap plastic around her arms and use them to help her swim in the water. The water couldn’t be drunk – it was filled with chemicals so you couldn’t drink it. It was just for fun.

You grab onto a large bottle floating next to you, to help you float. The gulls are still diving and for now, you’re still floating. You don’t know how to swim, you don’t know how to keep floating. So you hug the blue plastic animal and the plastic bottle, and you close your eyes and hold your breath each time a gull pushes your head into the water.

It’s this water, this unbreathable water that will kill you and the gulls know it, they knew it before you did. You hold tighter onto the bottle as a gull dives for your head again and small pieces of floating plastic brush your cheeks. The soft plastic is still protecting you, so you’ll stay like this until the gulls stop or you stop breathing.

Live by the plastic, die by the plastic – Great Grandmother said that once and you make a mental note to ask her what it means when you join her in the place after this one.

WORDS: B G ROGERS

ART: LAURA WILLIAMSON

Bethany’s first collection of stories, Kaleidoscopes in the Dark, is out now.