We heard there was an elephant buried in a Southland paddock. When we went to investigate, we found Sally.

Riversdale is a small town tucked between the Hokonui Hills and the Mataura River, just northwest of Gore. It has a nine-hole golf course, an annual Mixed Media Art Exhibition and a gloriously restored circa-1880 country hotel. It is also the burial site for Southland’s most famous (or only famous) pachyderm: Sally the elephant.

How Sally came to be interred in Riversdale was due to a series of unfortunate events. It started in the late 1950s, a golden era for travelling circuses, when exotic animals were the stars of the show. Sally was one of nine elephants travelling with the Bullen Brothers Circus. Born in the wild in 1935, the three-tonne Asian elephant had been part of the Bullen family for ten years by 1960, and at just 25 years old, she should have had many long years ahead of her. Asian elephants can live into their 50s. She was also valuable, said to be worth about £2000 at the time (the pound was the currency of Aotearoa New Zealand until 1967).

The Bullens were a famous Australian circus dynasty, known especially for their work with animals. Back then, larger circuses, which could involve close to 100 people, were a hugely popular form of entertainment, and they were often a family affair, the children pitching in with chores, performing and learning to handle the animals. Bullen’s Circus had been founded by Alfred Percival Bullen (known as “Perce”) and his brothers in the early 1920s; they started with a merry-go-round and worked their way up. By the time they were touring New Zealand with Sally, they were one the biggest circuses in the region. Elephants were the stars of the show, and they sometimes had as many as 14 on stage at once.

A flyer announcing the circus’ return to Australia after a 20-week tour of New Zealand described visiting 95 cities and towns and performing 217 shows for a total audience of 600,000. It was quite an enterprise. As the flyer pointed out: “Most people find, on an overseas trip, that one cabin-trunk is sufficient to carry their clothing. How would you like to carry over 100 animals (and nine of them elephants) – and 700 tons of luggage – and trouble with all of it except the nine trunks!”

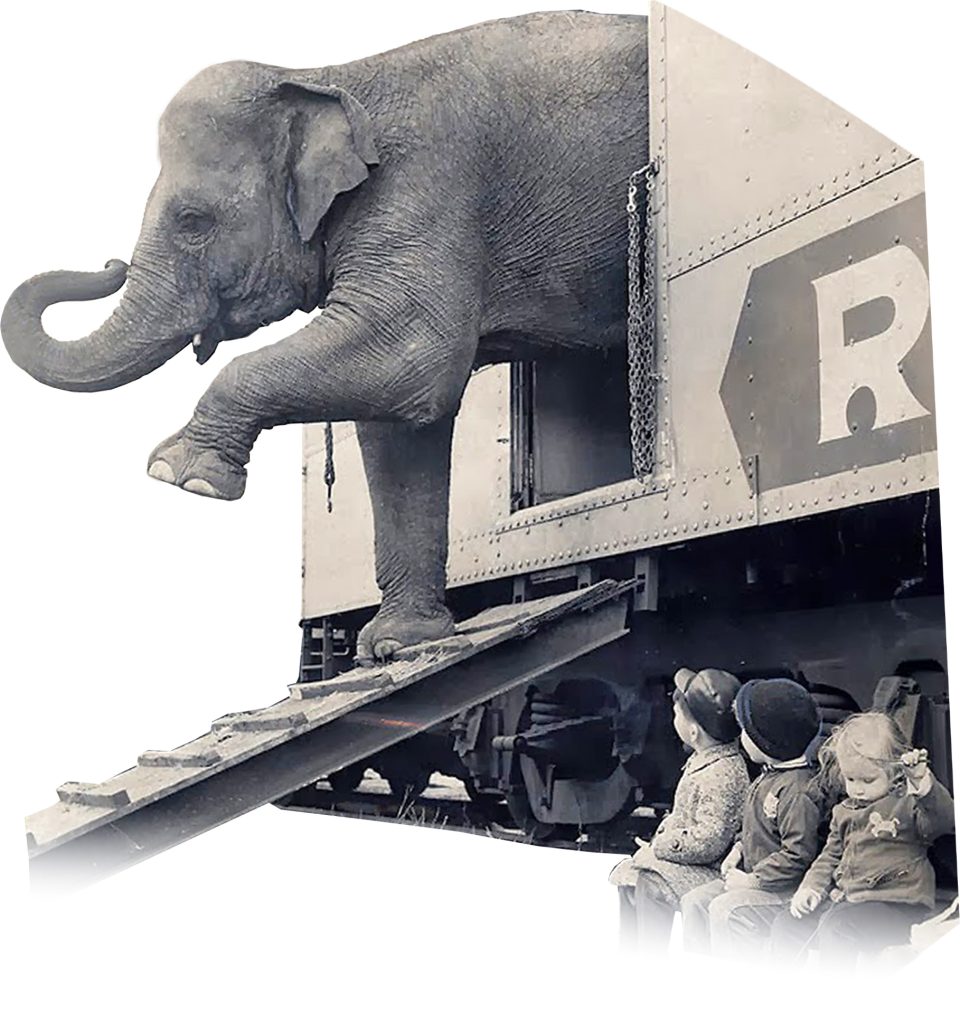

The townspeople of Riversdale grew excited as the circus rolled in on April 17, 1960, the atmosphere buzzing as the steam train pulled up to the local railway station from Gore. Each carriage on the red- and yellow-coloured locomotive was packed with performers, animals, trucks and equipment. Upon arrival, the elephants were guided off and tied up around the station; Sally was tethered at the railway siding, which is where the local Community Centre now sits.

PHOTO: Courtesy of Bullen’s Circus and Tony Ratcliffe

It was shortly after this that tragedy struck. A thirsty Sally was wetting her whistle by drinking from some nearby 44-gallon drums. Little did anyone know, the drums, which had filled up with water due to heavy rain, had once contained weedkiller. After no more than an hour, the sick elephant collapsed. Every effort was made to help Sally. Locals even pitched in to try and hoist the heavy beast upright, but the mix proved to be fatal. Sally passed away.

Before she was buried, a vet from Gore performed an autopsy. The local paper, the Mataura Ensign, reported that “the veterinarian found the beast’s skin to be about an inch thick, but surprisingly easy to incise.” Sally’s official cause of death was listed as poisoning by weedkiller.

It was a shock to both the members of the circus and the local community. Sally had been a hard worker, reliable and very gentle. Perce’s son, Stafford Bullen, the then-circus executive, told the Southland Times in 1960 that, “we have had Sally for 10 years and she was in the prime of her life. She was fully trained in circus performing, in transport work and in doing odd jobs around the place.” As Stafford’s wife Cleo, who had joined Bullen Brothers as a baton spinner when she was 14, explained to The Age years later, elephants like Sally even carried staff members between towns when the circus sometimes travelled on foot. “We walked about 35 miles a day … We had donkeys, horses, camels, elephants. So we’d ride the horses until we got sore, then we’d transfer and ride an elephant until we got sore, then we’d walk.”

It wasn’t all tough going. Stafford went on to make millions in the Australian animal safari business. Having people come drive through the animals was an easier ride. So in 1968 he opened Bullen’s African Lion Safari Park (showcasing seven elephants among the other wildlife), though the circus bug never left him. When he was 76, he hit the road with a travelling lion safari park and a show ring for one last tour under the Big Top.

After the Safari Park closed for good in 1988 (by then under the name Wanneroo Lion Park), its three remaining elephants, Siam, Bimbo and Sabu, went to live at the late Steve Irwin’s Australia Zoo. According to Steve, “Bullens have always been very proud of their elephants and very proud of their relationship with their elephants … they’ve adopted a family-type attitude towards their elephants and so the elephants reciprocate.” The trio became the final Bullen elephants to perform for the public.

As for Sally, after the autopsy her body was transported to her final resting place close to a duck pond on the Simmonds’ property on York Road, the closest farm to the incident. Children on bikes followed behind. Unveiled in 2019, a plaque commemorating Sally’s life sits on the Alex McLennan walking track not far from the paddock where she was laid to rest.

You may think this is a singular story. But wait. Sally isn’t the only elephant buried in Southland. Invercargill is the final resting place for another performing elephant, the Wirth’s Circus’ Betty, who died of tutu poisoning in 1950. Additionally, an elephant washed ashore at Doughboy Bay on Rakiura Stewart Island in the 1950s, reportedly a circus animal that had perished in transit and was cast overboard into the Tasman Sea. And, rumour has it, Riverton has an elephant gravesite too.

But it’s Sally who is remembered best – a big creature who still has a place in the hearts of the residents of a small town who made her part of their history. Just as “an elephant never forgets”, this elephant is not forgotten.

JESSICA ALLEN